Building Awareness of Health Research in the Mississippi Delta

When I was 17, my father died of lung cancer. At first, when he started coughing up blood, my mother and he thought he had a sore throat and a cold. His treatment of choice: Epsom salts and gargling with warm water. After a year, my mother made him go to a doctor, but it was too late. His cancer had spread everywhere.

Members of Les Belle Amies, a civic organization that raises money to help families in need, present a donation to Freddie White-Johnson for the Fannie Lou Hamer Cancer Foundation.

I only wish we knew then what the early signs and symptoms of cancer were. We lived on a cotton-and-soybean plantation in the rural Mississippi Delta. Literature and workshops on cancer did not exist. Transportation to a doctor was difficult, and there certainly was no mention of health or research in church. We were out there all alone with no support when it came to health care.

Today, I and others are working to change that for the people of the Mississippi Delta.

Through a Eugene Washington PCORI Engagement Award, my colleagues at the University of Southern Mississippi developed a training curriculum for community health advisors and community members on cancer awareness outreach and patient-centered research. The project I jointly led with my colleagues helped us to expand our decade of work in the Mississippi Delta to assist people in making better-informed decisions about their health care.

My father only had a first-grade education before working in the fields. When he was dying, he advised me to get an education and use it to “help the people like us.” I did, and have made it my life’s work by founding the Fannie Lou Hamer Cancer Foundation and becoming director of the Mississippi Network for Cancer Control and Prevention. Every day, my trained community health advisors and I provide cancer education and awareness to people like my father.

Healthy Expectations

Part of health education is teaching about the concept of research. Awareness is the first step needed before actively engaging community members in research, whether as study partners or participants. In the Delta, people my age automatically associate the term research with the infamous, unethical Tuskegee experiment, and they fear participation. This is why it’s key to thoroughly explain the research process in a way people can understand. PCORI’s Engagement Award supported our efforts to do that with our training materials on research’s potential to positively impact lives in our community.

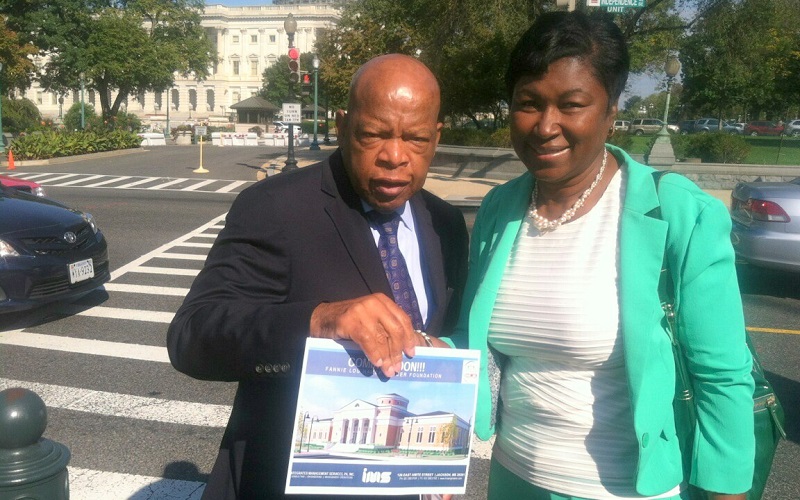

Freddie White-Johnson and Congressman John Lewis pose after a meeting in Washington, DC.

I find that once people in the Delta do understand the concept, those considering participating in a study are often most interested in knowing how it can benefit them. The expectation is that it will save their lives. In the Delta more generally, people tell us that they want to learn more about their risk factors and the symptoms of different diseases. PCORI has enabled us to hire people to go into areas we haven’t reached previously to spread knowledge about health and research. This has led to more people contacting us with an interest in cancer screenings. I’ve seen firsthand that what people learn about health risks has the power to change lives.

I always ask community members considering participation in research to think about their family members and what they would do to keep those who mean the most to them alive and healthy. If I had to give my DNA or whatever was necessary to a research project, and the findings could possibly save my father’s life, I would participate in a heartbeat.

I’ve seen firsthand that what people learn about health risks has the power to change lives.

In return, participants expect—and deserve—to know a project’s findings. And not just participants. PCORI knows that patients and the public need access to such information, so that they can use it to make decisions about their health. I share that vision, as I believe results can only be meaningful if they are available to the entire community.

To learn more about Freddie White-Johnson and her Engagement Award, see the feature article Improving Health in the Mississippi Delta through Powerful Engagement.

Making Findings Meaningful

When it comes to a rural community like ours, you have to use every medium that a resident might access to get the word out. The findings of studies should be made available by internet, radio, television, newspaper, and even billboards.

Following our PCORI-funded project, we presented our findings on community health advisors’ methods for cancer outreach to a packed room of more than 200 people, including project participants. We called the event “A Celebration of Progress.”

In another project, to reach our larger community, people who had been involved in the project did radio talk shows. Two doctors spoke on the show about community-based participatory research and why women were not getting mammograms. People in the community called in and asked questions.

With greater awareness about cancer specifically and health information generally, people can make better healthcare decisions. For those who remain skeptical or unaware of research’s power, I use every community event—even funerals, of which unfortunately we have many—to reach people.

Leave your footprint in the sand by getting involved in research and education programs, I tell people. Research may not save your life, but it may save your grandchild’s life or your great-grandchild’s life. My motto is: reach one, teach one, and we will save many.

To learn more about Freddie White-Johnson and her Engagement Award, see the feature article Improving Health in the Mississippi Delta through Powerful Engagement.

The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily those of PCORI.