Fighting to Stamp Out Tobacco Use among Underserved Populations

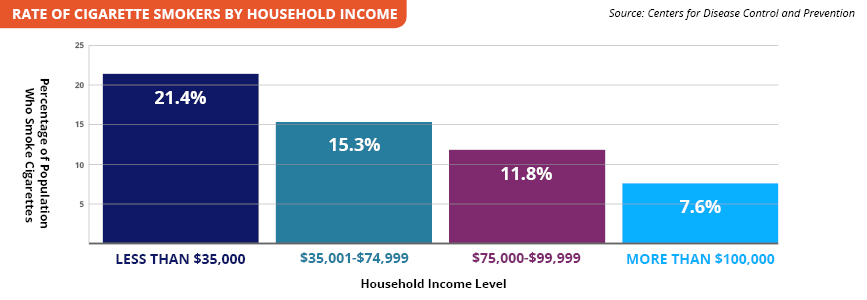

The United States has made great progress against the smoking epidemic over the past half-century, reducing the number of people who smoke from more than 40 percent of the population in the mid-1960s to around 14 percent today.

But that still leaves more than 34 million Americans using tobacco. And as with many health issues, underserved populations—including groups defined by race, ethnicity, comorbid health conditions, and low socioeconomic status—have shown markedly less improvement. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that more than 30 percent of Americans living below the poverty line smoke cigarettes.

“We have had amazing public health success with tobacco, but we failed to reach out to vulnerable populations,” said David Wetter, PhD, MS, of the University of Utah. “As a result, we’ve concentrated tobacco use among those groups.”

In response to this continued health epidemic, two PCORI-funded research teams are investigating interventions designed to help people in underserved populations access and engage in evidence-based tobacco cessation interventions and successfully quit smoking.

Connecting People with Evidence-Based Resources

Wetter’s University of Utah-based study is comparing strategies to engage tobacco users in cessation programs at community health centers (CHCs). These facilities provide primary care to millions nationally, the majority of whom are minorities and have incomes below the federal poverty level.

The study is enlisting more than 30 CHCs across Utah to test interventions that help patients who use tobacco to connect with Quitlines. Despite their name, Quitlines can be web- or text-based in addition to telephone-based, and they connect patients with counselors who offer an array of tools to help individuals stop using tobacco. Studies show that Quitlines are effective in helping people quit, but Wetter notes that only 1 to 2 percent of tobacco users access them annually.

"We are providing a way to help CHCs improve their patients’ health, but they don’t actually have to provide the treatment. We are all working together to create a win-win for providers, patients, and the whole stakeholder gamut."

- David Wetter, PhD, MS University of Utah

“It’s not that we don’t have an intervention that works—it’s that it simply is not utilized by a very large proportion of the population,” Wetter said. “So this study is focused on which strategies help patients to access and engage in treatment provided by Quitlines. CHCs have limited resources, so we designed interventions that become progressively more resource-intensive only for those individuals who may need more help.”

In the first-phase interventions, electronic health records (EHRs) trigger notifications that facilitate providers’ efforts to engage their patients with Quitlines. Among patients who do not engage with Quitlines, the interventions then progress to text messages, and finally to phone calls from counselors.

“If the clinic-level EHR interventions work for the patient, then hallelujah, we’re done,” Wetter said. “If not, we re-randomize them to another level of intervention.”

Wetter notes that most tobacco users want to quit, so he expects that a series of repeated reminders via text or phone call that help is available will eventually lead many patients to engage with a Quitline. “If we keep making a repeated offer of treatment, we know eventually we’ll hit many tobacco users at the right moment when they are ready to try to quit,” he said.

Wetter’s study was met with enthusiasm from the Utah Department of Health to CHCs to patients themselves. And because the CHCs—which work with limited resources—are merely connecting patients with Quitlines, there is much to be gained at little cost.

“We are providing a way to help CHCs improve their patients’ health, but they don’t actually have to provide the treatment,” Wetter said. “We are all working together to create a win-win for providers, patients, and the whole stakeholder gamut.”

Helping an Aging Population Kick the Habit

National guidelines recommend that older patients with heavy smoking histories get screened each year for lung cancer. Because half of patients eligible for this screening continue to smoke, these lung cancer screening programs also offer smoking cessation services. A University of Pennsylvania study led by Scott Halpern, MD, PhD, is seeking to find which intervention is most effective with this unique population.

“Patients eligible for lung cancer screening are much older than those who are participants in the overwhelming majority of smoking cessation trials conducted to date,” Halpern said. “So we don’t really have the foggiest idea of what smoking cessation interventions work best in this population.”

"We wanted to really focus on people for whom access to available smoking cessation interventions tends to be least, because that's where the health consequences tend to be greatest."

- Scott Halpern, MD, PhD University of Pennsylvania

The research team is recruiting 3,200 patients from underserved populations in four health systems in different regions of the country, and will follow them for up to 18 months to measure whether they stop smoking for six months straight.

“We wanted to really focus on people for whom access to available smoking cessation interventions tends to be least, because that’s where the health consequences tend to be greatest,” Halpern said.

The four interventions build on each other and are along a spectrum of least to most resource-intensive. The first group of patients will receive the Ask-Advise-Refer approach, in which clinicians ask smokers about their desire to quit smoking, advise them to quit, and refer them to resources that can help.

The second group will receive Ask-Advise-Refer and free access to nicotine replacement therapy, such as gum or patches, and US Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs to help with quitting. Providers will waive patients’ copays. The third group receives these benefits and a mobile health app that helps people imagine a future version of themselves that would be “both healthier if they quit, as well as wealthier given the money they would save by doing so.”

The final group will receive all these approaches and will also get paid if they quit. These individuals will benefit financially, and providers will save money long-term by avoiding costs that would arise from health problems if the patient had continued using tobacco.

Patients and other stakeholders helped design the study, from shaping the types of interventions tested to adding patient-reported outcomes, such as anxiety and urge to smoke, to the list of outcomes the researchers are collecting. Stakeholders are also helping to ensure patient-facing materials are at an appropriate reading level and culturally sensitive.

These two studies continue PCORI’s commitment to addressing healthcare disparities, an investment of more than $250 million, in an area that represents a critical health burden on the population.

“It’s critical to remind the public, healthcare providers, and policy makers that 480,000 people die each year in the United States because of tobacco use,” Wetter said. “It needs to remain in the public eye because it remains the single most preventable cause of death and disease in the country. If we forget about it and go on to everything else, we’re in trouble.”